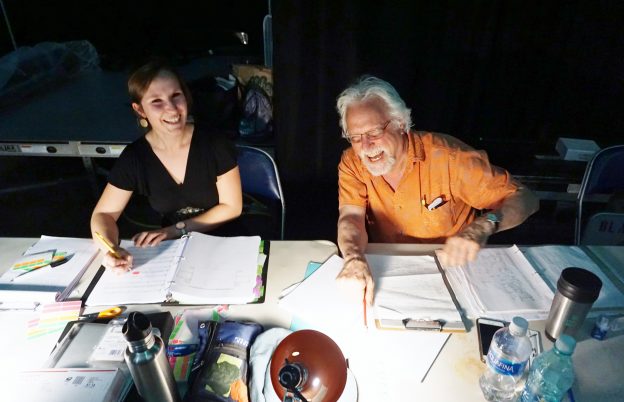

It takes a bunch of talented, skilled people that you never see or hear to pull these things off. There’s a lot going on that the audience doesn’t see. That’s what we are. We’re the people you don’t see. And we don’t want to be seen. We want to have these transitions happen and appear like magic, to some extent. Being the support role is what we do.” – HOT Director of Production Rob Reynolds

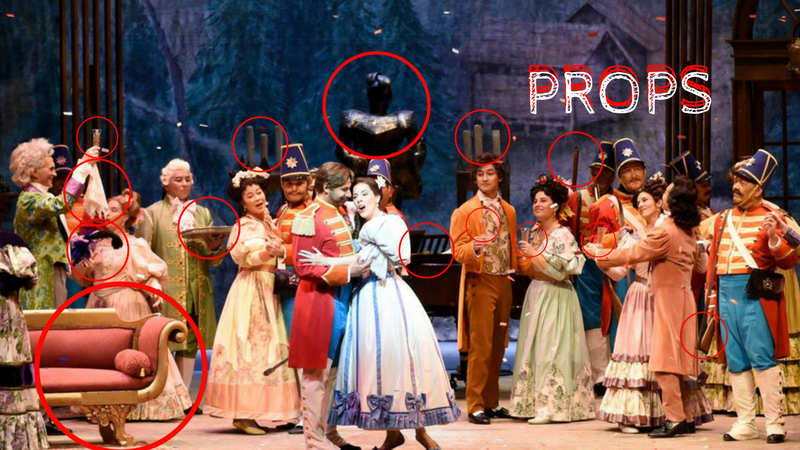

BECAUSE PRODUCING AN OPERA TRULY TAKES A VILLAGE, #HOTVILLAGE GIVES YOU AN INTIMATE LOOK AT ONE PIECE OF PRODUCTION FOR EACH HOT OPERA. IN THIS PIECE, HOT’S PROPS TEAM TOOK US BEHIND THE SCENES TO LEARN MORE ABOUT WHAT GOES INTO THE OBJECTS ONSTAGE THAT HELP TELL THE STORY OF THE DAUGHTER OF THE REGIMENT.

A Lot More Than Just “Fake Things”

During a backstage tour this month for students taking part in HOT’s residency programs, Prop Master Rick Romer posed a question to a group of 2nd and 3rd grade students: “What is a prop?”

The students considered the question for a few moments before one enthusiastically replied “a fake thing!”

Rick laughed, and then explained to the students that a prop is “anything that an actor or singer touches, holds, or uses as part of the scene.” And as each student thought about the definition, he exposed them to a series of “fake things” within HOT’s February production of Donizetti’s Daughter of the Regiment that have some very real stories to tell.

As an opera with a plot that features the French military, the audience won’t be surprised to see French flags waving and the chorus of soldiers carrying fake weapons. But behind the scenes, other props involve a process that is greater than what meets the eye.

As an opera with a plot that features the French military, the audience won’t be surprised to see French flags waving and the chorus of soldiers carrying fake weapons. But behind the scenes, other props involve a process that is greater than what meets the eye.

To demonstrate this to the students, Rick took out a silver platter topped with crystal glasses that were filled with champagne. He asked one young girl to carry it across the stage without spilling. As he saw her grow worried before attempting, he said, “Do you see what the problem is?”

He then explained how the prop team replaced the crystal with plastic glasses and glued metal washers to the bottom of each one to weigh them down. Finally, he demonstrated how a colored gel was placed into each cup to give the appearance of liquid from afar without the risk of spilling.

“I wanted the students to understand the process of problem solving, so they feel like they’re the ones discovering the solution or that they’re sharing in that process,” Rick said.

The Prop Master Rick has come a long way in his 50 year career in theatre and television since he created his first prop at 12 years old. His sister was cast as a maid in a school production, and she needed to carry a bag of groceries onto the stage for each production. Using just Lincoln Logs, Rick created a loaf of bread, celery, and other food items for the prop.

“I was in the house seeing my bag of groceries that I made, and it was like something clicked,” Rick said. “I really think that was my ‘aha’ moment.”

From Marcello’s easel in La Bohème to Rigoletto’s jester stick, props may not steal the show, but  behind them lies a unique process of troubleshooting and ingenuity. For Rick and his team of two assistants, problem solving is an integral part of the process of prop creation. And they enjoy the challenge.

behind them lies a unique process of troubleshooting and ingenuity. For Rick and his team of two assistants, problem solving is an integral part of the process of prop creation. And they enjoy the challenge.

“I love running props, because I like being in the process of the production,” said Prop Assistant Emi Yabuta as she painted a plastic pineapple to give it more depth. “Things happen and you have to solve problems on the spot. It’s wonderful. I love doing that.”

Emi begins each production by reading the opera’s libretto to learn more about its plot and characters. She believes that props should go a step further than simply being utilized by a character – they should help show the audience each character’s temperament.

In Act I of The Daughter of the Regiment, Tonio is hauled onto the scene by the French regiment in a burlap sack. After Marie explains that he saved her life, the soldiers allow him to have a drink with them, but he receives a smaller tin mug than the rest of them. Both the burlap sack and the smaller mug serve the purpose of showing that the Regiment is not yet on Tonio’s side.

But Emi’s favorite props are those of the chorus, because without them, the characters have no individuality.

“The chorus members have no names, so they have things to define them, like baskets or farm tools” she said. “It does change the coloring of the stage, because then it’s more than just a bunch of costumed people singing.”

The team’s favorite prop of the show, though, is one that Rick designed and created. Called the “crash box,” it is never seen and only heard. As the Duchess of Crackenthorpe leaves the home of The Marquise in Act II, she does so with a clamoring racket. The comical noise is created by a large wooden box filled with various metal entities rolling down steps backstage.

At the end of production, the crash box or the Lincoln Log bag of groceries probably won’t be what the audience remembers. And Rick doesn’t want them to.

“They shouldn’t take attention away from the music,” he said. “They’re simply there. They do their job, and they tell their story.”